A Graduate Course Disguised as a Trial by Fire

As an undergraduate, my university allowed students to take up to three graduate-level courses as electives. For my first, I chose Mechatronics, partly because it sounded intimidating, and partly because I suspected it would force me to learn things I didn’t yet know I needed.

The course itself was largely conceptual. The real grade came from a semester-long group project: build an autonomous robot capable of navigating a complex course and completing a multi-object task under uncertainty.

I was grouped with two PhD students. Both were racing to finish and defend their dissertations that same semester.

Which meant that very quickly a large fraction of the project landed on me.

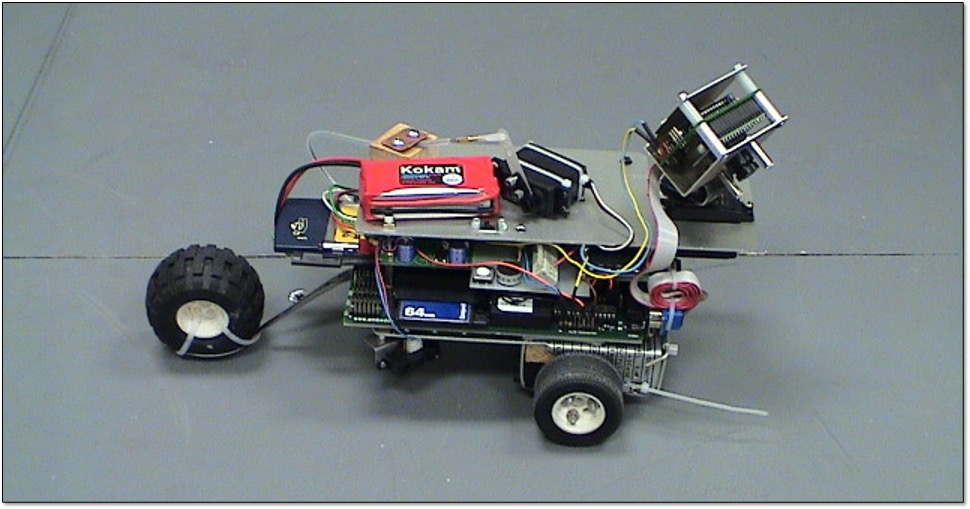

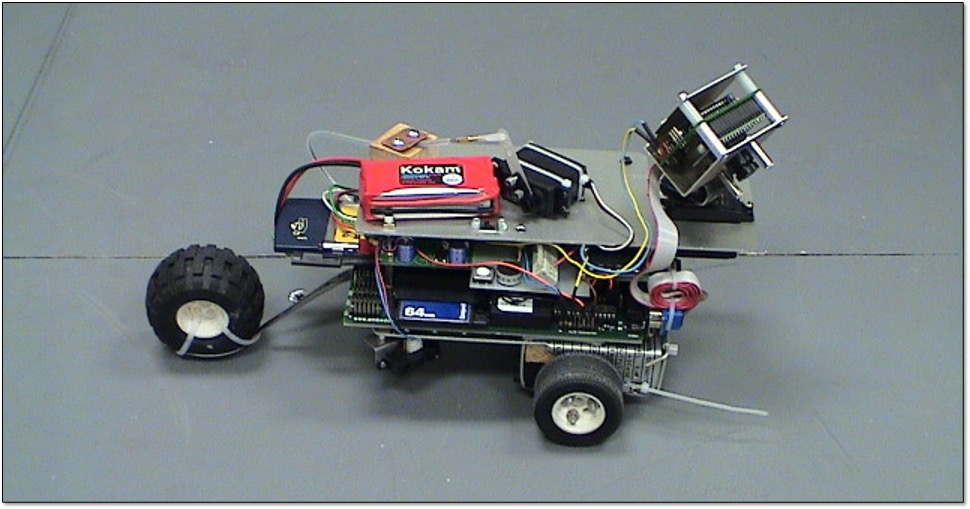

The final product of much sweat and many tears - “the Turtle”

The final product of much sweat and many tears - “the Turtle”

The Challenge: Turtle’s World

The robot (eventually named Turtle) had to autonomously navigate a course featuring:

- Ramps and uneven terrain

- A bridge with transparent decking

- Multicolored walls and boundary regions

- A “soccer goal”

- Multiple multicolored ping pong balls, only some of which were valid targets

Points were awarded for:

- Completing the full course

- Capturing the correct color balls

- Returning them to the goal

Points were deducted for grabbing the wrong balls.

No teleoperation. No resets.

The Hardware We Had (and Didn’t)

Our available hardware was minimal and unforgiving:

- A few DC motors and servo motors

- A CMUcam (RS-232 color vision camera)

- An ultrasonic rangefinder

- An embedded controller with limited ADC and PWM

- Batteries, wires, and lots of LEGO

- Whatever mechanical parts we could scrounge

No encoders. No IMU. No real odometry.

Just enough rope to hang ourselves.

Team Roles (and Reality)

Despite the pressure, the team dynamic worked remarkably well:

- One teammate was strong in software

- One was skilled with electronics

- I became:

- Mechanical designer

- Systems integrator

- Algorithm developer

I also became the person who had to decide which ambitious ideas to kill early.

Because it became clear very quickly:

Even with years, this problem would be hard.

We had months.

Mistakes (So Many Mistakes)

We made nearly every mistake you can make on a first autonomous system:

- Trusted open-loop wheel control far too long

- Assumed the CMUcam’s color thresholds wouldn’t drift when someone opened a window

- Mounted batteries so high that we lost traction on steep ramps

- Tried to do “precision” navigation with no real state estimation

- Underestimated how fast perception degrades as speed increases

Every subsystem interfered with every other subsystem.

Raising the camera improved visibility but raised the center of gravity.

Driving faster improved coverage but destroyed perception reliability.

Adding batteries improved run time but made ramps impossible.

It was systems engineering, whether we liked it or not.

The Night Everything Changed

About halfway through the semester, I was alone in the lab one evening, staring at camera data and motor commands, when something clicked.

We didn’t need precision.

We needed feedback.

Using the CMUcam, we could compute the horizontal offset of a ball’s image centroid from the center of the camera’s field of view. That offset could be treated as an error signal.

So I implemented a simple P-controller:

$$

e = x_{\text{ball}} - x_{\text{center}}

$$

$$

\omega_L = \omega_0 - K_p e

$$

$$

\omega_R = \omega_0 + K_p e

$$

That was it. No integral. No derivative. Just proportional feedback.

The robot homed in on the ball.

Once the image centroid dropped low enough in the frame (meaning the ball was close), we switched to open-loop forward motion and trapped the ball between the front wheels.

It worked.

The feeling when it worked the first time, and when I showed it to my teammates the next day and it worked again, was unforgettable.

That was the moment feedback control stopped being math and became behavior.

Iterating the Design - the Mouse and the Brick

We went through three major design phases over the semester, each one informed by painful lessons from the previous.

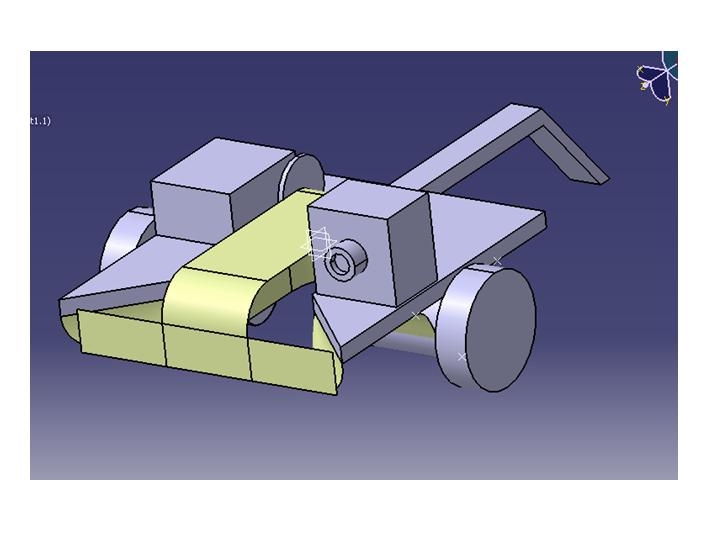

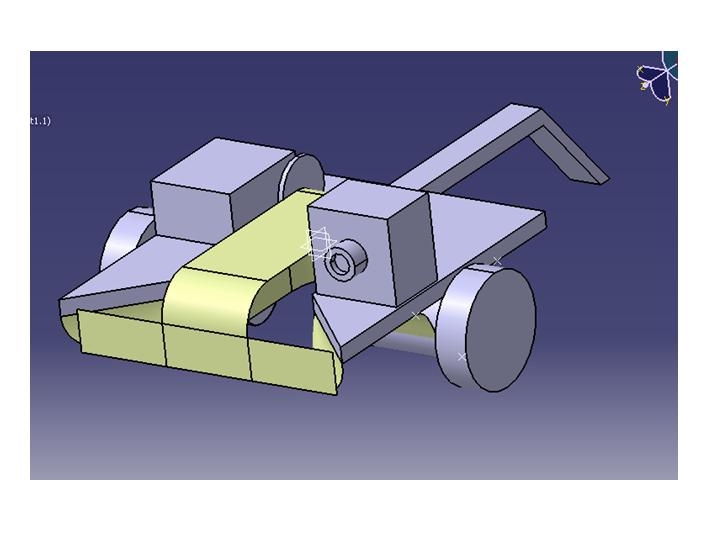

First design iteration: ambitious, unstable, and far too optimistic, “the Mouse”

First design iteration: ambitious, unstable, and far too optimistic, “the Mouse”

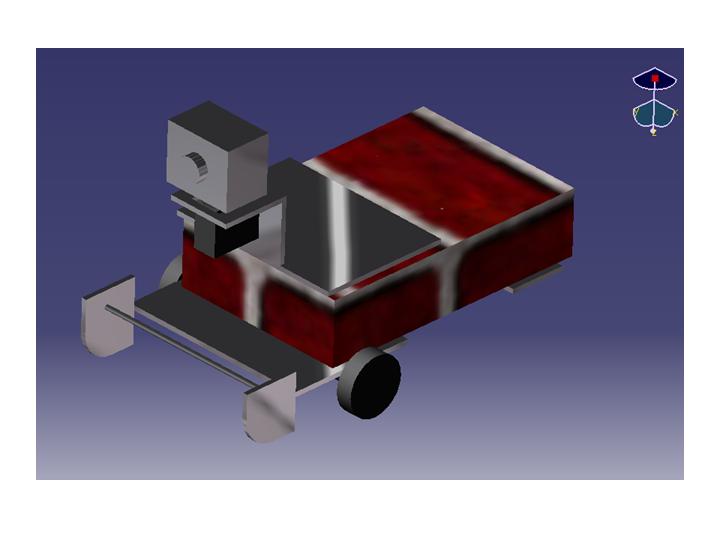

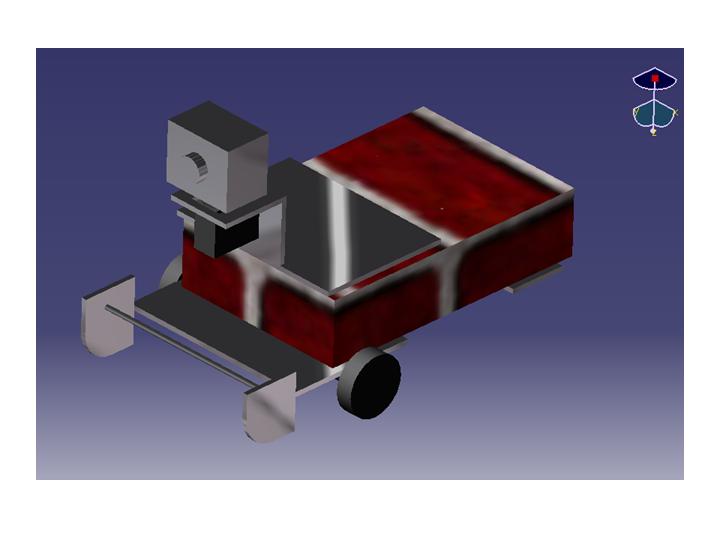

Second iteration: lower center of gravity, improved camera placement, and simplified mechanisms, lovingly referred to as “the Brick”

Second iteration: lower center of gravity, improved camera placement, and simplified mechanisms, lovingly referred to as “the Brick”

Each iteration stripped away complexity and increased robustness.

By the end of the semester, our robot was the only one that could reliably navigate the course, and the only one that could capture balls.

The Almost-Perfect Run

We completed the course.

We captured all the balls.

But we missed a perfect score.

We never had time to implement a proper ball ejector. Instead, we relied on a servo-actuated flap and an open-loop “charge the goal and brake” maneuver.

The balls got stuck on the chassis.

So close.

Only afterward did the professor admit that this was the fourth year he had taught the course that way … and that no team had ever completed the full challenge.

Why Turtle Still Matters to Me

This project cost me an enormous amount of time. Easily more than all my other coursework combined that semester.

And it was absolutely worth it.

It taught me:

- That feedback beats precision

- That hardware lies

- That perception and control are inseparable

- That simple equations can produce lifelike behavior

- That open-ended problems are where real learning happens

Most importantly, it set my trajectory.

This was the first time I took something messy, underdefined (and borderline impossible) and made it work through iteration, physics, and stubbornness.

Turtle didn’t just navigate a course.

It taught me how to engineer.

Ryan Blanchard PhD

Design, Research, Engineering, Data, Physics. I believe that few things in life are as rewarding as commiting yourself to a project to get something built. The feeling of seeing numerical and statistical models come to life in real-world hardware is just unbeatable.

The final product of much sweat and many tears - “the Turtle”

The final product of much sweat and many tears - “the Turtle” First design iteration: ambitious, unstable, and far too optimistic, “the Mouse”

First design iteration: ambitious, unstable, and far too optimistic, “the Mouse” Second iteration: lower center of gravity, improved camera placement, and simplified mechanisms, lovingly referred to as “the Brick”

Second iteration: lower center of gravity, improved camera placement, and simplified mechanisms, lovingly referred to as “the Brick”